The Science Behind Moisture, Spores & Home Air Quality

Indoor humidity is one of the most important — and most overlooked — environmental conditions affecting the health of a home. Although mold spores are present in nearly all indoor spaces, they typically remain dormant until the surrounding moisture level allows them to activate. Research from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) shows that nearly every mold species requires a certain threshold of humidity to germinate, spread, and begin producing allergens and mycotoxins. When a home stays above 60% relative humidity (RH), especially for extended periods, the microscopic water film on surfaces becomes sufficient for spores like Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Cladosporium to begin colonizing. This makes humidity control one of the most powerful, science-backed ways to reduce mold risk without chemicals or intensive structural repairs.

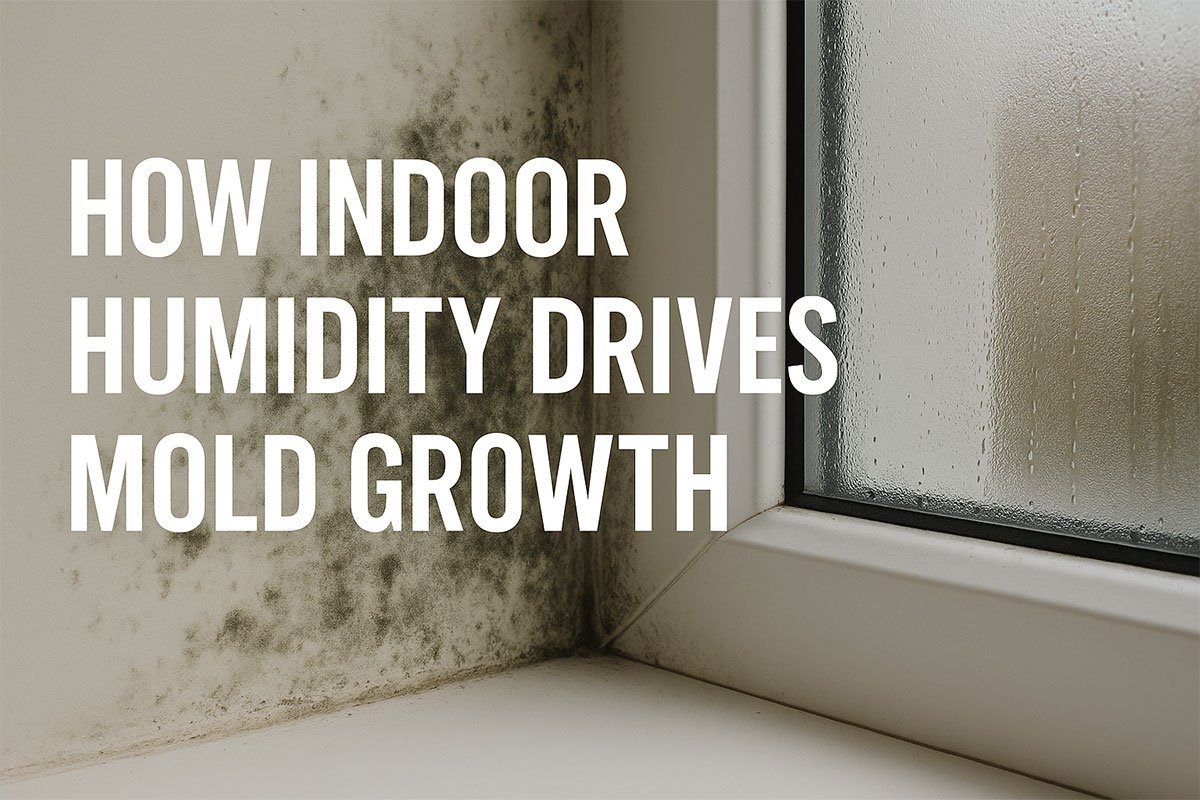

Understanding why humidity affects mold begins with the biology of spores themselves. Mold spores are resistant, lightweight particles that remain inactive until they take in enough moisture to perform cellular functions. At around 60–70% RH, spores start absorbing water through their outer shell, triggering metabolic activity and allowing them to send out hyphae — the thread-like structures that eventually form visible colonies. At even higher humidity levels, typically above 80–85%, moisture condenses on cool surfaces such as bathroom walls, window frames, basements, and behind furniture. This microscopic condensation works like irrigation for mold, supplying a constant source of water even when leaks are not present. Because modern homes are sealed tightly for energy efficiency, humidity often becomes trapped indoors, creating an ideal environment for mold to thrive.

While leaks and flooding are the most obvious causes of excessive moisture, scientific reviews repeatedly show that daily household activities contribute far more indoor humidity than people realize. Cooking, showering, drying laundry inside, running aquariums, or even breathing in poorly ventilated rooms can significantly increase moisture levels. A family of four can release over three gallons of water per day into indoor air simply through routine living. Once humidity rises, mold does not need much else — just a porous surface, a moderate temperature, and enough time to grow unnoticed.

To reduce the risk of mold growth, homeowners can take several science-supported actions that target humidity, airflow, and moisture accumulation:

Early Warning Signs of High Indoor Humidity

- Windows fogging or forming droplets during the morning

- Musty odors in closed rooms or closets

- Peeling paint, bubbling drywall, or dark shadows on walls

- Condensation forming on cold surfaces (pipes, metal fixtures)

- Fabrics, carpets, or bedding feeling damp to the touch

Effective Ways to Lower Humidity Backed by Research

- Maintain indoor humidity between 30% and 50% using a hygrometer

- Run bathroom and kitchen exhaust fans for at least 20–30 minutes after use

- Seal air leaks around windows and doors to prevent humid outdoor air from entering

- Use a dehumidifier in basements, crawlspaces, and rooms with poor airflow

- Increase ventilation by opening windows on opposite sides of the home when weather permits

- Repair plumbing leaks and insulate cold pipes to prevent condensation

Keeping humidity under control is not just about preventing surface mold; it’s also crucial for long-term indoor air quality. Once humidity remains elevated for several days, the home’s microbiome begins to shift. Studies show that high-moisture indoor environments support the growth of mold species that release allergens, spores, and microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs). These compounds can contribute to respiratory irritation, headaches, and increased asthma symptoms, especially in children or sensitive individuals. Even small mold patches hidden behind furniture, inside HVAC ducts, or under carpeting can generate a measurable impact on indoor air.

Long-term moisture control not only prevents mold growth but also protects building materials. Drywall, wood framing, insulation, and carpets can all deteriorate when exposed to repeated high humidity. Over months or years, this can lead to structural weakening, foul odors, and costly remediation work. By keeping humidity in the recommended range and ensuring consistent airflow through living spaces, homeowners create an environment that is naturally resistant to mold without relying on heavy chemical use or frequent deep-cleaning routines.

Managing humidity remains one of the simplest, most evidence-based strategies for maintaining a healthy home. With proper ventilation, dehumidification, and awareness of early warning signs, mold growth becomes far less likely, and indoor air quality improves significantly. Homes that maintain 30–50% relative humidity experience dramatically fewer mold problems, better occupant comfort, and longer-lasting building materials — a strong return on a small investment in monitoring and ventilation.

Scientific Sources

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — “A Brief Guide to Mold, Moisture, and Your Home.”

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) — Mold & Moisture Health Studies.

- ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers) — Indoor humidity standards and ventilation guidelines.

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health — Indoor air quality and household moisture research.

- Building Science Corporation — Moisture dynamics in buildings and mold prevention studies.